Holistic Measures for Occupational Therapy Practitioners to Assess Sexuality-Related Occupations: A Scoping Review

Disability is a natural part of human experience. Every person will experience temporary or permanent functional limitations, including difficulty completing a meaningful occupation, task, or activity (WHO, 2024). An estimated 16 percent of the global population is significantly disabled (WHO, 2024). In the United States alone, 27 percent of adults are disabled. Of this population, 10.8 percent have difficulty with activities (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (CDC, 2023). Even with over one-fourth of the United States population being disabled, the centuries-long challenges faced by people with physical disabilities persist (Seervai et al., 2019).

Historically, people with physical disabilities were marginalized, dehumanized, and desexualized. For example, in the 1860s, the Ugly Laws objectified people with physical disabilities by allowing a public ban of any person who was “diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object” (Nielsen, 2012). Decades later, during the Coolidge presidency, the eugenics movement led to the forced sexual sterilization of over 65,000 “physically defective” Americans (Nielsen, 2012). In the United States, 31 states plus Washington, D.C., still have laws permitting forced sterilization. Two states, Alaska and North Carolina, have laws banning forced sterilization in most cases, yet these same laws also restrict people with physical disabilities’ autonomy of choice in the matter (NWLC, 2022). In a 2023 systematic review of 19 peer-reviewed studies and 10 grey literature sources, six themes emerged within the youth with physical disabilities population, including sexuality resources neglecting the sexual rights of the population, parents of this population fearing for their child’s sexual vulnerability, healthcare providers reporting feelings of unpreparedness in addressing sexuality within this population, sexuality-related discrimination, dismissed and unrecognized agency of this population’s sexuality, and lastly, the diverse identities and sexual experiences of this population (Giles et al., 2023). A 2021 qualitative study highlighted clinicians’ hesitancy to address sexuality (i.e., taboo), their unpreparedness to address client exposure to sexuality, and addressing parental concerns around sexuality (Lindsay et al., 2021). Often, people with physical disabilities are perceived in extremes, such as being asexual, sexually vulnerable, or sexually deviant. These polarizing social constructions of people with physical disabilities further perpetuate the view that people with physical disabilities are outside of the social norm (Giles et al., 2023). Erotic privilege is defined as a form of privilege afforded only to certain types of bodies within a given culture (Fielding, 2021). In American and Western European cultures, these bodies are “typically white, cis, able-bodied, thin, tall, and between the ages of 18-35. Bodies that do not conform to... one or more of these cultural ideals are erotically marginalized” (Fielding, 2021).

People with physical disabilities experience challenges in several areas of sexuality and intimacy-related occupations. For example, people with physical disabilities who have complex communication needs face barriers related to social and environmental factors, prohibiting socialization and networking, further contributing to deficits in social participation and leading to limited opportunities to develop intimate relationships and social isolation (Sellwood, Raghavendra, & Walker, 2022). In addition, people with physical disabilities have reported a lack of educational and healthcare resources, a lack of self-agency related to their sexual health, and a lack of competent healthcare providers as barriers to sexual healthcare (Giles et al., 2023). Historically excluded groups such as queer, trans, and nonbinary folx experience increased rates of marginalization, leading to intersections of discrimination, inequality, and health disparity (Mulcahy et al., 2022). People with physical disabilities who identify as transgender or nonbinary reported barriers to health and related financial management occupations, as well as fear around sexuality-related client factors. This population reported a lack of insurance, cost of care, fears related to disclosing sexuality and gender identity, discrimination by healthcare providers, and structural barriers as challenges to addressing their unmet healthcare needs (Mulcahy et al., 2022). These challenges expand beyond the client’s intrinsic and personal factors into healthcare systems and how occupational therapy practitioners treat individuals with physical disabilities.

Occupational Therapy and Sexuality

Occupational therapy practitioners’ internal biases, policies, and practices in healthcare systems, and other contextual factors create barriers to adequate and appropriate care related to sexuality and intimacy occupations (Lepage, Auger, & Rochette, 2020). A 2020 study of Canadian occupational therapy practitioners reported that while most practitioners agreed that addressing sexuality was within their scope of practice, few did so in their practice, citing discomfort in addressing sexuality and lack of knowledge around the subject as barriers (Young et al., 2020). The overarching themes of healthcare incompetence, lack of access, and fears related to societal perceptions and norms perpetuating stigma or discrimination complicate the experiences of this population and lead to a gap in rightful, competent, inclusive sexual healthcare.

In occupational therapy, screening tools are the first step to identify clients’ needs in a particular domain (Boone, Henderson, & Dunne, 2022). After that, further evaluation measures can inform occupational therapy practitioners about the clients’ functional ability and performance in specific occupations, and help guide interventions (Asaba et al., 2017).

This scoping review aims to explore and identify instruments available to assess sexuality-related occupations from a holistic perspective for adults over the age of 19 to inform occupational therapy practitioners about participation.

Methods

We explored self-report holistic measures for adults over 19 that assess one’s participation and performance in sexuality-related occupations (Mak & Thomas, 2022; Tricco et al., 2018), considering person factors, performance factors, and contextual factors. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018).

Identifying the Research Question

In this review, sexuality-related occupations include occupations related to one’s sexual activity, sexual function, sexual health and hygiene (including urogenital and gender-affirming care), and family planning. A holistic approach to these occupations considers the whole person through the lens of the Occupational Therapy Sexual Assessment Framework (McGrath et al., 2020), encompassing person factors, performance factors, and contextual factors. Person factors include client factors (values, beliefs, spirituality, sexual knowledge, sexual self-view), body functions (sexual interest, sexual response), and body structures (i.e., anatomical structures) involved in sexuality-related occupations. Performance factors include performance skills and performance patterns (roles, routines, habits).

Identifying Relevant Studies

We conducted searches of 6 databases, including CINAHL, Embase, Medline-OVID, PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science. Our searches included articles published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2010 and April 2025. The search strategies were made considering title, abstract, and keywords using the following keywords selected in consultation with a university informationist: assess*; continence; gender affirm*; gender identit*; gender identity; instrument*; occupational therap*; occupational therapy; pelvic floor; scale*; screen*; sexu*; sexu* arousal; sexu* behavior; sexu* dysfunction; sexu* health; sexu* hygiene; sexu* interest; sexu* pain; sexu* safety; sexual arousal; sexual behavior; sexual dysfunctions, physiological; sexual health; tool* * (see Table 1 in the Supplemental Appendix, for search strategies). Records not in English were excluded. The lead author screened titles, abstracts, and keywords for inclusion criteria. Both authors reviewed full-text records for inclusion criteria and resolved disagreements through discussion to reach consensus.

Selecting Studies

Journal articles were included if they were published between January 2010 and April 2025, were Level II or III evidence (American Occupational Therapy Association, 2022), mentioned the use or application of a measure (e.g., assessment, instrument, scale, screening tool) that considers the holistic approach to the person as described above, including person factors, performance factors, and environmental factors during sexuality-related occupations (as listed in the Occupational Therapy Sexual Assessment Framework; McGrath et al., 2020), were published in English, and used human subjects. Articles were excluded if they were not peer-reviewed, the measures used or applied were not validated, the subjects were not patients (e.g., clinicians), or the subjects were not over the age of 19.

Data Charting

Consistent with recommendations by Mak & Thomas (2022), we created an Excel spreadsheet to chart the following data from articles during the full-text review (see Appendix Table 2): Names of authors, year of publication, research design, population, and measures mentioned. A second Excel sheet charted the total assessment measures mentioned to map the following data (see Appendix Table 3): measure name, whether the measure was validated, and met person factors, performance factors, occupations, and environmental factors as previously defined.

Results

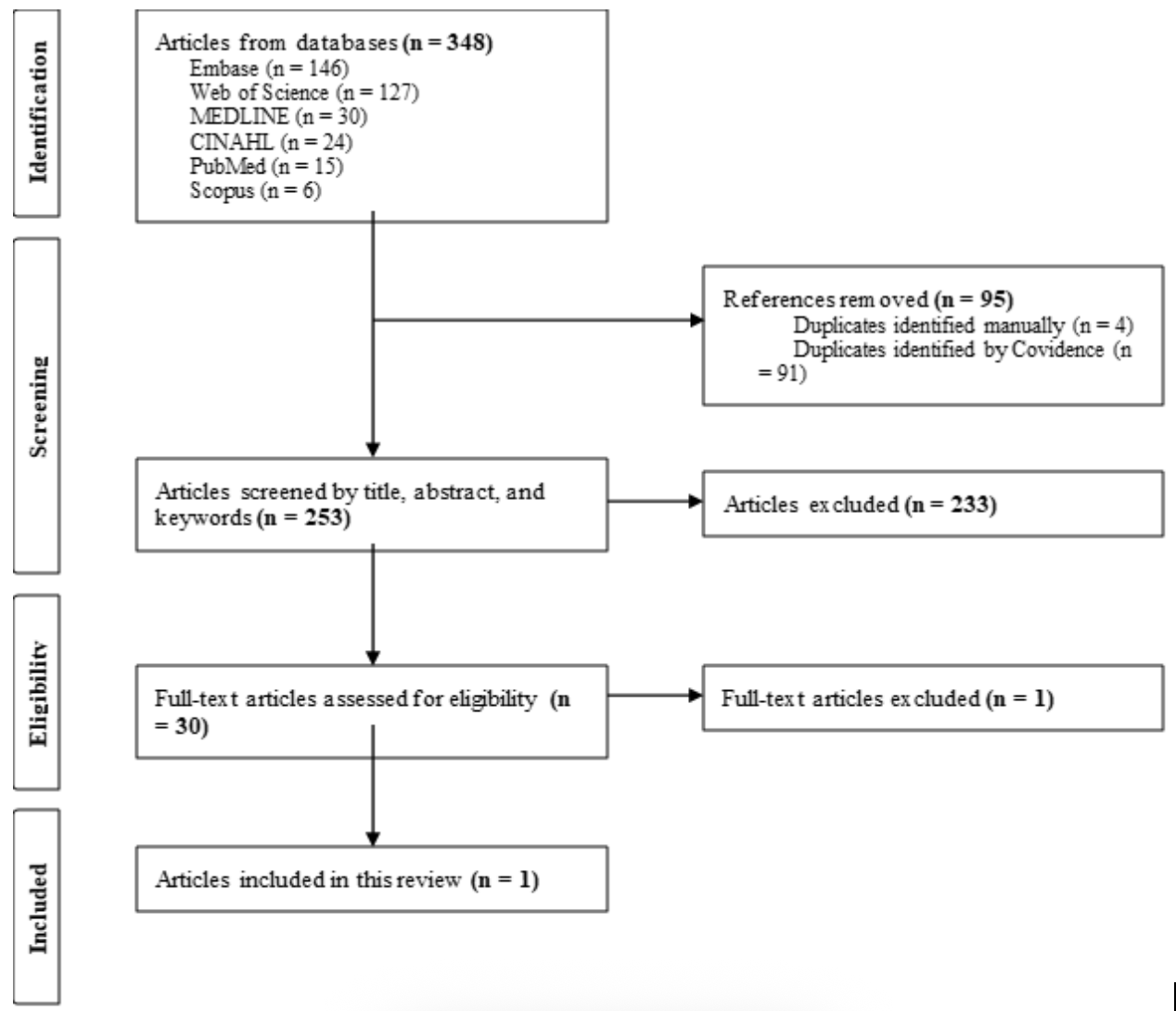

We identified 348 articles from the search results. After duplicate files were removed, the lead author screened titles, abstracts, and keywords of all articles and excluded 223 articles because they did not meet eligibility criteria. We then reviewed the remaining 30 articles in full text and mapped the data. Each article was reviewed for measures used, then those measures were charted and examined to ensure they were validated and met holistic criteria as previously defined and validated. Following the charting of data, 29 articles were excluded. The remaining 1 article (Walker et al., 2020) produced a measure that was holistic as previously defined. It is noteworthy that while this measure has not yet been validated per eligibility criteria, it was still included in this scoping review as it is the only holistic measure designed for clients to self-report about sexuality-related occupations and guide occupational therapy interventions.

This scoping review revealed a significant gap in validated, holistic assessment measures for evaluating participation and performance in sexuality-related occupations. Of 348 articles identified, only one measure, the Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI), met the eligibility criteria for a holistic approach. However, it has not yet been validated and did not meet the inclusion criteria. Most excluded studies relied on measures that addressed narrow or isolated aspects of sexuality, such as physiological function or distress, without considering the broader person, performance, and contextual factors essential to occupational therapy practice. Many measures were also not client-centered, lacked validation, or focused on clinician perspectives rather than those of individuals engaging in these occupations. These findings emphasize the need for the development and validation of inclusive, occupation-centered assessment measures. Such measures are essential for occupational therapy practitioners to support client-centered care and address sexuality-related occupations in a comprehensive and just manner.

Note: From the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” by D. Moher, A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman; PRISMA Group, 2009, PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI)

Walker et al. (2020) developed a comprehensive, holistic measure called the Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI). The OPISI uses a structured, client-centered approach to discussing sexuality and intimacy with clients, identifying challenges they might face in sexuality-related occupations, and helping occupational therapy practitioners guide interventions that promote quality of life and occupational engagement (Walker et al., 2020). The measure is divided into 3 primary components: a self-screen, an in-depth self-assessment, and a performance measure. The self-screen contains 13 items and aims to initiate discussions about sexuality and intimacy, affording the client understanding that these topics are appropriate and acceptable within the clinical setting (Walker et al., 2020). The in-depth assessment contains 122 items across 7 domains and seeks to provide deeper insight into specific areas of concern that were identified during the self-screen. These domains include sexual activity, intimacy, sexual interest, sexual response, sexual self-view, sexual expression, and sexual health and family planning (Walker et al., 2020). The last component is a performance measure that contains 28 items that establish a client’s baseline performance and identify self-perceived changes over time in ability, satisfaction, understanding, and confidence related to sexuality and intimacy. (Walker et al., 2020). In total, the assessment consists of 163 items, of which 135 are self-report items and 28 are practitioner-assisted items. As of 2025, this measure has only undergone phase one development and has not yet been validated.

Discussion

This scoping review sought to identify validated, holistic assessment measures that support occupational therapy practitioners in evaluating client participation in sexuality-related occupations. Despite a thorough search across six major health science databases and the application of robust eligibility criteria, no validated measures were found that comprehensively evaluate sexuality-related occupations through a holistic, occupational therapy lens. However, one measure, the Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI), met all eligibility criteria for a holistic framework, but it has not yet been validated. The findings of this review emphasize a significant gap in the literature and clinical practice measures. Sexuality is a key domain of human occupation and well-being, yet it remains marginalized in occupational therapy measures and practice. The absence of validated holistic measures not only limits occupational therapy practitioners’ ability to address this domain but also contributes to ongoing occupational injustices, particularly for individuals with disabilities and those with intersecting marginalized identities. The current assessments explored do not adequately reflect the complex interplay of personal, performance, and contextual factors influencing sexuality-related occupations.

The OPISI, while promising, presents several limitations. Its comprehensive nature, with 163 items spanning three components, raises concerns about clinical feasibility, particularly in time-limited practice settings. Additionally, the OPISI does not explicitly include or affirm the experiences of transgender and nonbinary individuals, revealing a critical oversight in inclusivity. Without measures that consider the full spectrum of gender and sexual identities, occupational therapy practitioners risk perpetuating systemic erasure and exclusion in clinical assessment and intervention planning. Furthermore, the findings reflect broader issues in healthcare and occupational therapy education, where sexuality is often underrepresented or treated as a taboo topic. As noted in previous studies, many practitioners report discomfort or lack of training in addressing sexual health (Young et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2021). This discomfort may contribute to the lack of demand for such measures, as well as the insufficient development and validation of measures like OPISI.

The integration of a validated, inclusive, and holistic measure into occupational therapy practice is essential to uphold the profession’s commitment to client-centered, justice-oriented care. Assessment measures must be feasible, sensitive to diverse identities and experiences, and aligned with the occupational therapy practice framework. Moreover, researchers and practitioners must engage in participatory measure development, ensuring that historically excluded populations have a voice in the design and validation of assessments that affect their care. Ultimately, this review highlights an urgent call to action: to develop and validate holistic, occupation-centered assessment measures that encompass the full spectrum of sexuality-related occupations and identities. Such measures will enable occupational therapy practitioners to engage in meaningful conversations, collaborate with clients in setting goals, and design interventions that support holistic well-being.

Limitations

This scoping review was conducted by two authors, which may have introduced limitations in terms of study selection bias, reduced methodological rigor, and limited diversity of expertise. Although efforts were made to ensure consistency and transparency in screening and data charting, the absence of a third reviewer may have impacted the resolution of disagreements and the comprehensiveness of the literature coverage.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Madison Jurgens, Information Specialist at the Columbia University Medical Center Library, for her logistical recommendations and contributions to this work.

References

Aiyegbusi, O. L., Cruz Rivera, S., Roydhouse, J., Kamudoni, P., Alder, Y., Anderson, N., Baldwin, R. M., Bhatnagar, V., Black, J., Bottomley, A., Brundage, M., Cella, D., Collis, P., Davies, E. H., Denniston, A. K., Efficace, F., Gardner, A., Gnanasakthy, A., Golub, R. M., Hughes, S. E., … Calvert, M. J. (2024). Recommendations to address respondent burden associated with patient-reported outcome assessment. Nature medicine, 30(3), 650–659. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02827-9

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2022). Levels and strength of evidence. https://www.aota.org/practice/manage/evidence/strength-levels

Andring, L., Maturen, K. E., Jolly, S., & Elshaikh, M. A. (2023). The role for an enhanced recovery pathway for gynecologic cancer patients receiving brachytherapy: A prospective clinical trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 117(2), e421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.07.1079

Asaba, E., Nakamura, M., Asaba, A., & Kottorp, A. (2017). Integrating Occupational Therapy Specific Assessments in Practice: Exploring Practitioner Experiences. Occupational therapy international, 2017, 7602805. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7602805

Auger, C., Demers, L., Gélinas, I., & Noreau, L. (2023). Sexuality after a stroke: Adaptation and cross-cultural validation of two assessment tools to address factors influencing French-Canadian clinicians' practice. Sexuality and Disability, 41(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-022-09738-5

Barnaś, E., Krupińska, A., Kraśnianin, E., & Raś, R. (2012). Psychosocial and occupational functioning of women in menopause. Menopause Review/Przegląd Menopauzalny, 11(4), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.5114/pm.2012.30237

Bass, J. D., Baum C. M., Christiansen C. H. (2015). Interventions and outcomes: The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) occupational therapy process. In Christiansen C. H., Baum C. M., Bass J. D. (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation and well-being (4th ed.), 57–80. Slack, Inc.

Boone, A. E., Henderson, W. L., & Dunn, W. (2022). Screening Tools: They're So Quick! What's the Issue?. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 76(2), 7602347010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.049331

Brown, D. A., Nelson, M., & Claffey, A. (2014). Quality of life outcomes and service user evaluation of a pilot physiotherapy rehabilitation programme for people living with HIV. HIV Medicine, 15(S3), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12198

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). Disability impacts all of us. Retrieved May 12, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

Chaves, K. M., Serrano-Blanco, A., Ribeiro, S. B., & Lessa, J. L. M. (2013). Quality of life and adverse effects of olanzapine versus risperidone therapy in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly, 84(1), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-012-9233-3

Denning-Kemp, G., Ashburn, A., & Taylor, R. (2019). Should physiotherapists and occupational therapists be part of the comprehensive geriatric assessment clinics within the outpatient setting? Age and Ageing, 48(Supplement_2), ii1–ii16. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz103.07

dos Santos, M. D., de Oliveira, W. A., & de Souza, M. F. (2020). From permanence to quality of life: Sexual orientation and gender identity of students in a higher education institution in the Brazilian northeast. Bioscience Journal, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.14393/BJ-v36n1a2020-45577

Ewer-Smith, C., McLean, S., & Richardson, J. (2018). Let's talk about sex: An occupational therapy clinical evaluation about the importance of sexual intimacy issues in the treatment of patients with persistent pain. Australian Journal of General Practice, 47(11), 757–761. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-03-18-4523

Faten, A., Ben Hmida, M., & Ben Salah, M. (2018). Body image disorder in 100 Tunisian female breast cancer patients. La Tunisie Médicale, 96(1), 35–41.

Gerbild, H., Larsen, C. M., & Graugaard, C. (2017). Health care students’ attitudes towards addressing sexual health in their future professional work: Psychometrics of the Danish version of the Students’ Attitudes Towards Addressing Sexual Health Scale. Sexual Medicine, 5(4), e224–e231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.10.001

Gewirtz-Meydan, A., Levkovich, I., Pinto, G., & Ayalon, L. (2022). Discomfort in discussing sexual issues: Developing a new scale for staff at long-term care facilities for older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 48(9), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20220808-01

Giles, M. L., Juando-Prats, C., McPherson, A. C., & Gesink, D. (2023). “But You’re in a Wheelchair!”: A Systematic Review Exploring the Sexuality of Youth with Physical Disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 41, 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1001/s11195-022-09769-5

Gross, D. P., Knupp, H., & Esmail, S. (2011). The utility of measuring sexual disability for predicting 1-year return to work. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(11), 1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2011.06.021

Hydeman, J. A., Uwazurike, O. C., Adeola, O., & Beaupin, L. K. (2014). Assessment of cancer survivors' needs through the survivorship screening tool. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0340-9

Kamińska, A., Baranowska, A., & Starczewski, A. (2019). Sexual function specific questionnaires as a useful tool in management of urogynecological patients: Review. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 234, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.01.008

Kasar, S., Dwivedi, A. K., & Khandare, P. M. (2023). Impact of occupational therapy interventions on sexual dysfunction in epilepsy: A case report. Cureus, 15(12), e51153. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51153

Killeen, M. E., Skidmore, E. R., & Terhorst, L. (2020). Severity of post-intensive care syndrome in adult ICU survivors is associated with prior mental health diagnosis: A regression analysis. Journal of Critical Care, 55, 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.10.019

Kumar, M. A., & Shweta, N. (2024). Effect of video modeling with simulation on improving menstrual hygiene skills for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Cureus, 16(1), e39040730. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39040730

Labuschagne, E., & van Niekerk, M. (2019). Sensory processing of women diagnosed with genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder: A research proposal. BMC Research Notes, 12, 577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4612-6

Lepage, C., Auger, L. P., & Rochette, A. (2020). Sexuality in the context of physical rehabilitation as perceived by occupational therapists. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(19), 2739–2749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1715494

Limbutara, W., Sangsawang, B., & Sangsawang, N. (2023). Patient-reported goal achievements after pelvic floor muscle training versus pessary in women with pelvic organ prolapse: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 43(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2023.2181061 Taylor & Francis Online

Lindsay, S. (2021). Healthcare providers' perspectives with addressing sex-related issues and sexual identity within pediatric rehabilitation: A qualitative study. Disability and health journal, 14(3), 101093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101093

Mak, S., & Thomas, A. (2022). Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. Journal of graduate medical education, 14(5), 565–567. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00621.1

McDonald, K. L., Smith, J. A., & Lee, R. Y. (2024). Patient satisfaction with a pelvic floor pre-habilitation program in patients treated with definitive pelvic chemoradiation for squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Supportive Care in Cancer, 32(5), 2345–2353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07654-2

McGrath, M., Sakellariou, D., & Hilton, C. (2020). The Occupational Therapy Sexual Assessment Framework (OTSAF): A new tool for addressing sexuality. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(3), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619886810

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mulcahy, A., Streed, Jr., C. G., Wallisch, A. M., Batza, K., Kurth, N., Hall, J. P., & McMaughan, D. J. (2022). Gender Identity, Disability, and Unmet Healthcare Needs among Disabled People Living in the Community in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2588). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052588

National Women’s Law Center (NWLC). (2022). Forced sterilization of disabled people in the United States. Retrieved September 18, 2024, https://nwlc.org/resource/forced-sterilization-of-disabled-people-in-the-united-states/

Nielsen, K. E. (2012). A disability history of the United States. Beacon Press.

Pătru, D., Popescu, M. R., & Dumitrescu, D. (2021). Influence of multidisciplinary therapeutic approach on fibromyalgia patient. Romanian Journal of Military Medicine, 124(2), 123–130.

Pigott, J. S., Armstrong, M. J., Davies, N., & Walters, K. (2024). Factors associated with self-rated health in people with late-stage Parkinson’s and cognitive impairment. Quality of Life Research, 33, 2439–2452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03703-2 SpringerLink

Polo, K. (2022). The Screen of Cancer Survivorship-Occupational Therapy Services (SOCS-OTS): A Delphi study for tool validation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(3), 7603205020. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.049569

Scheurich, A., Smith, M. T., & Kanner, A. M. (2024). Characteristics and outcomes of youth with functional seizures attending intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment. Epilepsy & Behavior, 136, 108963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2023.108963

Scott, D. A., & Brown, K. (2012). Resumption of valued activities in the first year post liver transplant. Occupational Therapy International, 19(4), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1338

Sellwood, D., Raghavendra, P., & Walker, R. (2022). Facilitators and barriers to developing romantic and sexual relationships: Lived experiences of people with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 38(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2022.2046852

Serpa, R. O., Sanhudo, A., & de Souza, M. C. (2016). Let's talk about sex: Examining staff comfort in discussing psychosexual functioning in a rehabilitation setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(11), 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1061603

Seymour, L. M., & Wolf, T. J. (2014). Participation changes in sexual functioning after mild stroke. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 34(2), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20131217-01 Sage Journals

Thomas, H. (2016). Sexual function after stroke: A case report on rehabilitation intervention with a geriatric survivor. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation, 32(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/TGR.0000000000000097

Tibaek, S., Gard, G., Dehlendorff, C., Iversen, H. K., Biering-Sørensen, F., & Jensen, R. (2017). Is pelvic floor muscle training effective for men with poststroke lower urinary tract symptoms? A single-blinded randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Men's Health, 11(5), 1460–1471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315610816 Sage Journals+2PMC+2Sage Journals+2

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., ... Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Walker, L., & Davis, K. (2020). Development of the Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI): Phase one. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 34(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2020.1727118

Wilcock, A. A. (1998). Reflections on doing, being, and becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65, 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174x

World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Disability. Retrieved September 18, 2024, https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability

Young, K., Dodington, A., Smith, C., & Heck, C. S. (2020). Addressing clients' sexual health in occupational therapy practice. Canadian journal of occupational therapy. Revue canadienne d'ergotherapie, 87(1), 52–62.https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419855237

Table 1

Search Strategies

CINAHL

(TI "Occupational Therapy" OR AB "Occupational Therapy" OR KW "Occupational Therapy") AND (TI (Sexu*) OR AB (Sexu*) OR KW (Sexu*) OR TI ("Sexual Behavior") OR AB ("Sexual Behavior") OR KW ("Sexual Behavior") OR TI ("Sexu* Behavio*r*") OR AB ("Sexu* Behavio*r*") OR KW("Sexu* Behavio*r*") OR TI ("Continence") OR AB ("Continence") OR KW ("Continence") OR "Gender Identity" OR TI ("Gender Identit*") OR AB ("Gender Identit*") OR KW ("Gender Identit*") OR “gender affirm*" OR TI ("gender affirm*") OR AB ("gender affirm*") OR KW ("gender affirm*") OR "Pelvic Floor" OR TI ("Pelvic Floor") OR AB ("Pelvic Floor") OR KW ("Pelvic Floor") OR "Sexual Arousal" OR TI ("Sexual Arousal") OR AB ("Sexual Arousal") OR KW ("Sexual Arousal") OR "Sexual Dysfunctions" OR TI ("Sexual Dysfunctions") OR AB ("Sexual Dysfunctions") OR KW ("Sexual Dysfunctions") OR "sexu* dysfunction" OR TI ("sexu* dysfunction") OR AB ("sexu* dysfunction") OR KW ("sexu* dysfunction") OR "Sexual Health" OR TI ("Sexual Health") OR AB ("Sexual Health") OR KW ("Sexual Health") OR "Sexu*Health" OR TI ("Sexu* Health") OR AB ("Sexu* Health") OR KW ("Sexu* Health") OR "Sexu* hygiene" OR TI ("Sexu* hygiene") OR AB ("Sexu* hygiene") OR KW ("Sexu* hygiene") OR "Sexu* interest" OR TI ("Sexu* interest") OR AB ("Sexu* interest") OR KW ("Sexu* interest") OR "Sexu* pain" OR TI ("Sexu* pain") OR AB ("Sexu* pain") OR KW ("Sexu* pain") OR "Sexu* safety" OR TI ("Sexu* safety") OR AB ("Sexu* safety") OR KW ("Sexu* safety")) AND (TI (Instrument*) OR AB (Instrument*) OR KW (Instrument*) OR TI (Tool*) OR AB (Tool*) OR KW (Tool*) OR TI (Assess*) OR AB (Assess*) OR KW (Assess*) OR TI (Screen*) OR AB (Screen*) OR KW (Screen*) OR TI (Scale*) OR AB (Scale*) OR KW (Scale*))

PubMed

("Occupational Therapy"[Mesh] OR "Occupational Therap*"[tiab]) AND (Sexu*[tiab] OR "Sexual Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Sexu* Behavio*r*"[tiab] OR Continence[tiab] OR "Gender Identity"[Mesh] OR "Gender Identit*"[tiab] OR "gender affirm*"[tiab] OR "Pelvic Floor"[Mesh] OR "Pelvic Floor"[tiab] OR "Sexual Arousal"[Mesh] OR "Sexu* Arousal"[tiab] OR "Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological"[Mesh] OR "Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological"[Mesh] OR "sexu* dysfunction"[tiab] OR "Sexual Health"[Mesh] OR "Sexu* Health"[tiab] OR "sexu* hygiene"[tiab] OR "sexu* interest"[tiab] OR "sexu* pain"[tiab] OR "sexu* safety"[tiab]) AND (Instrument*[tiab] OR Tool*[tiab] OR Assess*[tiab] OR Screen*[tiab] OR Scale[tiab])

Embase

('occupational therapy'/exp OR ‘occupational therap*’:ti,ab,kw) AND (Sexu*:ti,ab,kw OR ‘Sexual Behavior’/exp OR ‘Sexu* Behavio*r*’:ti,ab,kw OR Continence:ti,ab,kw OR 'gender identity'/exp OR ‘Gender Identit*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘gender affirm*’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘Pelvic Floor’/exp OR ‘Pelvic Floor’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘Sexual Arousal’/exp OR ‘Sexu* Arousal’:ti,ab,kw OR 'psychosexual disorder'/exp OR 'sexual dysfunction'/exp OR ‘sexu* dysfunction’:ti,ab,kw OR 'sexual health'/exp OR ‘Sexu* Health’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sexu* hygiene’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sexu* interest’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sexu* pain’:ti,ab,kw OR ‘sexu* safety’:ti,ab,kw) AND (Instrument*:ti,ab,kw OR Tool*:ti,ab,kw OR Assess*:ti,ab,kw OR Screen*:ti,ab,kw OR Scale*:ti,ab,kw)

Medline-OVID

(exp Occupational Therapy/ or "Occupational Therap*".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf.) and (Sexu*.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Sexual Behavior/ or "Sexu* Behavio*r*".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or Continence.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Gender Identity/ or "Gender Identit*".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or "gender affirm*".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Pelvic Floor/ or "Pelvic Floor".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Sexual Arousal/ or "Sexu* Arousal".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Sexual Dysfunctions, Psychological/ or exp Sexual Dysfunction, Physiological/ or "sexu* dysfunction".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or exp Sexual Health/ or "Sexu* Health".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or "sexu* hygiene".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or "sexu* interest".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or "sexu* pain".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or "sexu* safety".ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf.) and (Instrument*.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or Tool*.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or Assess*.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or Screen*.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf. or Scale.ti,ab,cl,oa,kw,kf.)

SCOPUS

TITLE-ABS-KEY("occupational therap?") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Sexu? OR "Sexu? Behavio?r" OR Continence OR Gender Identit? OR "gender affirm?" OR "Pelvic Floor" OR "Sexu? Arousal" OR "sexu? dysfunction" OR "Sexu? Health" OR "sexu? hygiene" OR “sexu? Interest” OR "sexu? Pain” OR “sexu? Safety”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(Instrument? OR Tool? OR Assess? OR screen? OR scale?)

Web of Science

Occupational Therap* AND Sexu* OR "Sexual Behavior" OR "Sexu* Behavio*r*" OR Continence OR "Gender Identity" OR "Gender Identit*" OR "gender affirm*" OR "Pelvic Floor" OR "Pelvic Floor" OR "Sexual Arousal" OR "Sexu* Arousal" OR "Sexual Dysfunctions" OR "Sexual Dysfunction" OR "sexu* dysfunction" OR "Sexual Health" OR "Sexu* Health" OR "sexu* hygiene" OR "sexu* interest" OR "sexu* pain" OR "sexu* safety" AND Instrument* OR Tool* OR Assess* OR Screen* OR Scale

Note: If available, the following filters were used to narrow search results before screening: date range (“2010” to “2025”), subjects (“humans”), language (published in “English”), population (“adults” and/or “19+”), publication type (“academic journal”).

Table 2

Full-text articles and reasons for exclusion

Andring et al. (2023)

Evidence: Level II

Measures: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), and “European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-CX24)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence.

Auger et al. (2023)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Determinants for Implementation Behaviour Questionnaire (DIBQ), Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude towards Sexuality Scale (KCAASS), and “Knowledge, Comfort, Approach and Attitude towards Sexuality Scale for Stroke (KCAASS-Stroke)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Barnas et al., 2012

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Kupperman Index, World Health Organization Quality of Life - Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Brown et al. (2014)

Evidence: Level III

Measures: Functional Assessment of HIV Infection (FAHI) Scale

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

Chaves et al. (2013)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Quality of Life Scale validated for Brazil (QLS-BR), Udvalg for Kliniske Undersogelser Side Effect Rating Scale

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Denning-Kemp et al. (2019)

Evidence: Level V (Retrospective)

Measures: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

dos Santos et al. (2020)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: World Health Organization Quality of Life - Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Ewer-Smith et al. (2018)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Faten et al. (2018)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales (HADS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Gerbild et al. (2017)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Students’ Attitudes Towards Addressing Sexual Health (SA-SH)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Gewirtz-Meydan et al. (2022)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Discomfort in Discussing Sexual Issues (DDSI) with Older Adults scale

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Gross et al. (2011)

Evidence: Level III

Measures: Sexual Behavior item of the Pain Disability Index

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

Hydeman et al (2014)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Survivorship Screening Tool (SST)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Kaminska et al. (2019)

Evidence: Level V

Measures: Body Image in the Pelvic Organ Prolapse (BIPOP), Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Gender and Sexuality Identity Scale (GSIS), Gender and Sexuality Identity Scale-20 (GSIS-20), Genitourinary Relationship Distress Scale (GRISS), King's Health Questionnaire (KHQ), Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI-20), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire-7 (PFIQ-7), Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12), Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire- (PISQ-31), Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire-International Urogynecology Association Revised (PISQ-IR), Pelvic Quality of Life (P-QoL), Sexual Activity Questionnaire (SAQ)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Kasar et al. (2023)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire -Male (CSFQ-M), Generalised Anxiety Disorder -7 (GAD -7) questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire -9 (PHQ-9), Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory31 (QOLIE-31) questionnaire

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Killeen et al. (2020)

Evidence: Level III

Measures: Patient Health Questionnaire -9 (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) Questionnaire, (IESR), Sexual Complaint Screener for Women and Men (SCSR), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

Kumar, M.A. &Shweta, N. (2024)

Evidence: Level II

Measures: Menstrual Practice Needs Scale (MNPS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

Labuschagne et al. (2019)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Adolescent/Adult Sensory History (ASH), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales (HADS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Limbutata et al. (2023)

Evidence: Level II

Measures: Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire/International Urogynecology Association Revised (PISQ-IR), Prolapse Quality of Life Questionnaire (P-QOL)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

McDonald et al. (2024)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQoL) instrument, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Pǎtru et al. (2021)

Evidence: Level II

Measures: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Fibro Fatigue (FF) scale

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Pigott et al. (2024)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Functional Disability Inventory (FDI)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Polo, K. (2022)

Evidence: Level Ib (Validation Study)

Measures: Screening of Cancer Survivorship-Occupational Therapy Services (SOCS-OTS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Scheurich et al. (2024)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: EuroQol 5-Dimensions, 3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Scott & Brown (2012)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Short Form-36 (SF-36)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Serpa et al. (2016)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Sexual Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (SABS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Seymour, L.M. & Wolf, T.J. (2014)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Quality of Sexual Function scale, Stroke Impact Scale (SIS)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Thomas, H. (2016)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Quality of Sexual Function Scale, Stroke Impact Scale

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined; wrong level of evidence

Tibaek, S. et al. (2017)

Evidence: Level II

Measures: Danish Prostate Symptom Score (DAN-PSS-1)

Excluded: Measure used is not holistic as defined

Walker et al. (2020)

Evidence: Level IV

Measures: Occupational Performance Inventory of Sexuality and Intimacy (OPISI)

Excluded: Measure used is not validated